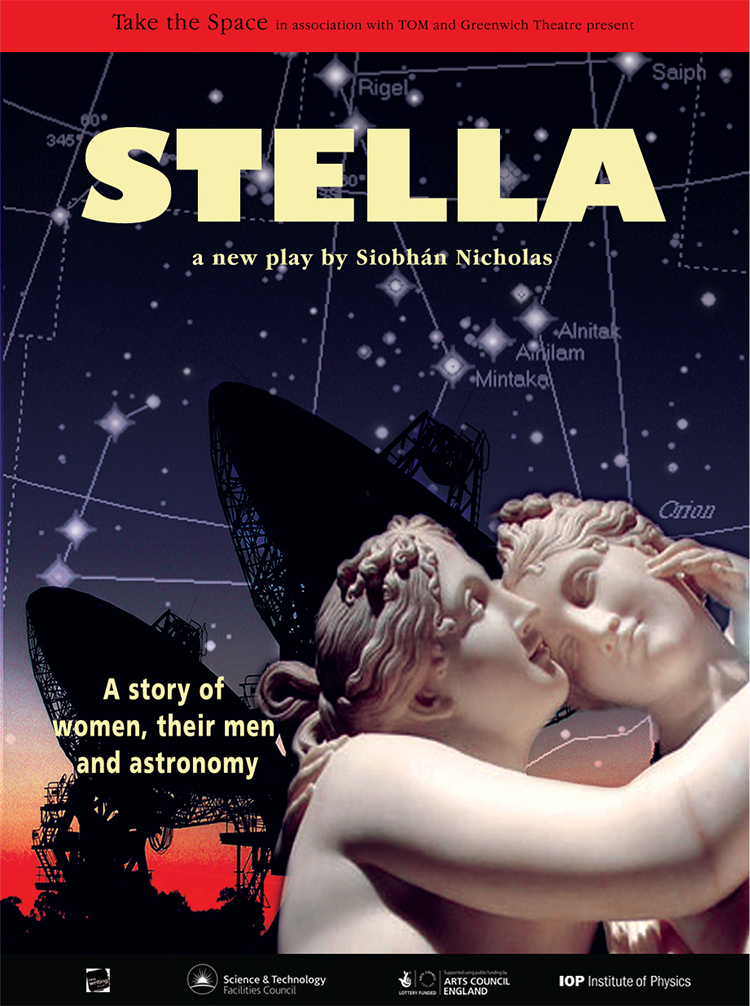

Reviews for Take the Space's Production of STELLA

The Guardian

A play about astronomer Caroline Herschel sets the record straight, performed reading at Paines Plough 2012

Reviewer: John Vidal

One of the least expected successes in London's West End last week was STELLA by Take the Space. The three actors wore their own clothes, hadn't learned any lines, and there were only about 20 people in the invited audience who met in a circular room high above the Aldwych.

Moreover, the show was hardly a barrel of laughs, being about female astronomers – notably the tiny, forgotten, angry 18th century Caroline Herschel. But I have to admit, the audience choked on the bared emotions and the wonderment of people seeing deep space for the first time.

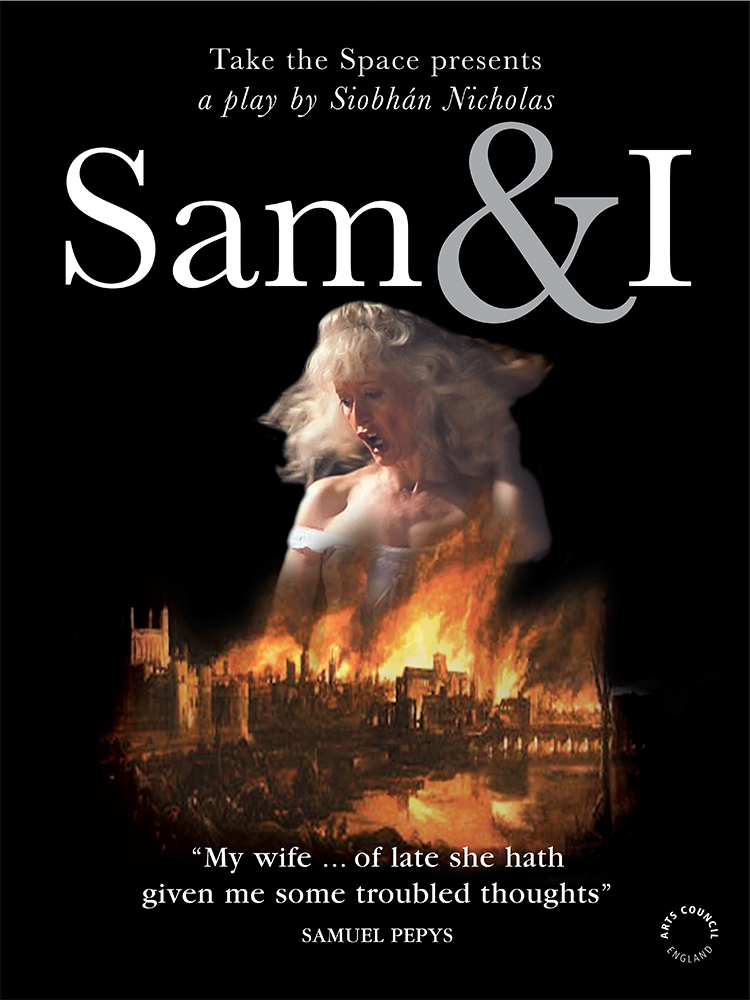

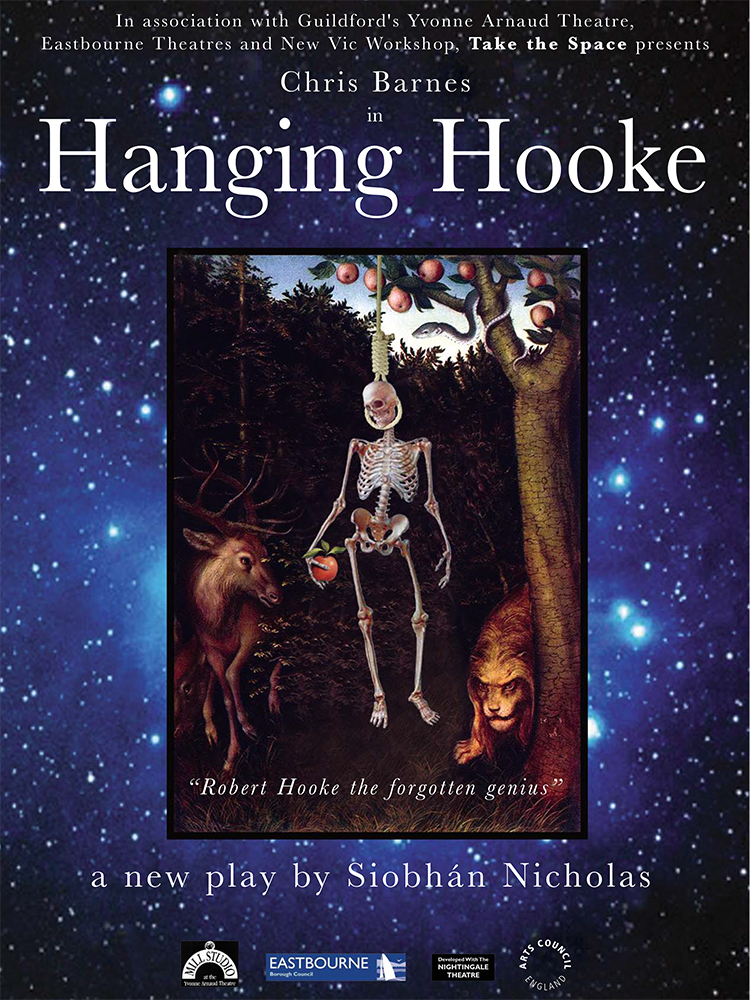

This was a performed, one-off reading of Stella, a new play by Irish actor-playwright Siobhán Nicholas, who appears to be inventing a new theatre form that we might call "revelatory early science". After their show about 18th century Royal Society chair and diarist Samuel Pepys, she and Chris Barnes – a former National Theatre actor and Barnum and Bailey circus clown – have been touring a play about "England's Leonardo": Robert Hooke.

Stella is different. It explores the fevered world of women astronomers, especially the 18th century brother and sister relationship of Caroline and William Hershel. William discovered Uranus and its two moons and conducted the first systematic search of the heavens. Caroline – nominally his assistant – not only made his tea and telescopes, but discovered eight comets and 11 nebulae and won the Royal Astronomical Society's Gold Medal. Between them, they could be said to have laid the foundations of modern astronomy - a point made with Nicholas's parallel story of a modern woman astronomer

But while the history books are full of William's achievements, William's thoughts and William's point of view, they are remarkably silent on Caroline's life work, referring to her "meek devotion" to him and, grudgingly, to her role as his assistant.

Nicholas went directly to her journals and found not just the mystery of eight missing pages, but a remarkable, rueful, humorous woman who came to Britain and, in just a few years, mastered a new language, learned mathematics, became a professional soprano singer, and ended up a far more rigorous cataloguer and arguably a greater discoverer of the cosmos than her brother.

Early European science is brilliantly funny, intellectually revolutionary and intensely passionate. But this is a part of the scientific and historical cosmos that is barely recognised and even less explored. Hopefully, someone will now commission this work and we will all get the chance to see it in full costume and with all the bells and whistles of a major theatre.

The Guardian

Wednesday 18 September 2013 at Mill Studio, Guildford

Reviewer: Lyn Gardner

Siobhan Nicholas looks to the stars in an exploration of the role played by women as thinkers and scientists throughout history.

You have probably heard of William Herschel, the 18th-century astronomer credited with discovering Uranus. But what about his sister, Caroline? She was a gifted singer who kept house for her brother, helped him in his work, both as a composer and astronomer, and still managed to find the time to discover eight comets and 11 nebulae, and painstakingly map the skies.

Yet like so many female scientists of earlier eras, she often only appears in the history books as a footnote to the life and work of a man.

Invoking the spirit of Hypatia of Alexandria, the 4th-century scholar of mathematics and astronomy, murdered by Christian fanatics who feared her knowledge, Siobhan Nicholas's ambitious play hops between the 21st and 18th centuries, as well as the UK and the Arab spring Egypt of 2011, as it probes the ever-shifting role of women as thinkers, scientists, wives and mothers.

The estimable Kathryn Pogson plays Jessica, a radio astronomer, whose daughter is in Egypt as the Tahrir Square demonstrations gather momentum. Jessica's husband, Bill, has recently accepted a job in Hamburg and wants his wife to accompany him. As Jessica researches Caroline's life and discovers crucial pages missing from Caroline's diary, she begins to understand how much that devoted sister gave up for her brother. Hundreds of years on, have we made as much progress as we think?

The reclamation of women's history is admirable, there is much to enjoy in the clever entwining of theatre and science, and the final moments in which the characters gaze into space and the future has undeniable emotional clout.

The Public Review

Minerva, Chichester 20/02/2015

Reviewer : Steve Turner

Drawing directly from the journals of Caroline Hershel, Siobhan Nicholas has created a thought provoking work exploring the world of 18th century astronomy and its parallels with the present day.

Jessica, a modern day astronomer, has taken a commission to write a magazine article about Hershel, one of the earliest female scientists and an astronomer like herself. As she reads through the journals, the action on stage switches to 18th century Bath and the lives of Caroline Herschel and her brother William.

As the two stories unfold we begin to see the similarities between the situations the two females find themselves in.

Present day Jessica is expected by her husband to follow him to his new job in Hamburg, Hershel in 18th century Bath is expected to forego her career as a soprano in order to support her brother in his endeavours as a composer, conductor and scientist. Jessica’s husband is taken aback when she tells him that she will not follow him to Hamburg, but she is insistent and also somewhat upset that he thinks she should just drop everything. She questions why she should always be the one to give things up, something that the 18th century Caroline also comes to ask later in the work.

The three cast members seem completely at ease with their characters, writer Nicholas portrays Caroline as a determined scientist and devoted sister, invoking much sympathy with her impassioned outburst when she is forced to move out after her brother marries. She is also delightfully scatty as the slightly eccentric Penelope, keeper of the Hershel museum in Bath.

As modern day scientist Jessica, Sian Webber has the same drive for accuracy and integrity displayed by her 18th century counterpart. In a touching scene near the end of the work the tearful message she leaves for her daughter is perfectly delivered and seems to come straight from her heart.

Chris Barnes flits between the two time periods as Jessica’s husband, and Caroline’s brother, emphasising the similarities between the two – both rather self-obsessed, single minded and a little misogynistic, yet played with warmth to make them both believable and likeable.

The play grabs the attention of the audience in the opening scene – an argument between Jessica and Bill – and does not let go until the emotion charged ending.

Presented on a simple set featuring a round table with two round chairs, symbolic of a planet and two moons, and with the cast in white moving around like the comets discovered by Hershel, the whole work is full of imagery.

Perhaps the most significant metaphor, reflecting the main theme of the play, is that of twin stars, one shining brightly with the other less visible. Much like Hershel and his sister, who has been somewhat overlooked despite her significant contribution to astronomy.

BurySpy.com

We Review STELLA - Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds

Reviewer: Jen O’Reilly

“There is nothing that makes our differences so insignificant as the infinite starry sky above our heads.”

These words from Dr Olja Panić of the Institute of Astronomy from the University of Cambridge speaking after the performance last night echoed the overwhelming message of eternal and timeless wonderment, charm and beauty of the night skies similarly conveyed in this stellar theatrical production about women and their influence on astronomy and our understanding throughout history of the stars.

On stage for one more night only at the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds, Siobhán Nicolas’ graceful and mesmerising one-act story about the passions and astronomical achievements of the eighteenth century Caroline Herschel seamlessly and poetically incorporated also the experiences and discoveries of other female scientists, ranging from the fifth century Hypatia at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina to the twentieth century Nobel prize winner Professor Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

Herschel (performed by Nicolas) was a passionate singer and musician who settled in Bath from Germany with her brother William (Chris Barnes) in the mid eighteenth century and became an accidential scientific heroine through her work supporting his interest in astronomy and nebulae.

She was the first woman to be recognised for her contributions by the Royal Astronomical Society and receive a number of other scientific accolades in later life. Stella portrays her extraordinary works in the context of her relationship with her family members and her true desire to perform Handel’s Messiah rather than play second fiddle to her brother.

At the same time, elements of the life of modern astrophysist Bell Burnell and the tragic fate of the female mathematician, astronomer and philosopher Hypatia are expertly and poignantly interwoven into a wider tale involving a more contemporary astronomer and her family - Jessica Bell James played by Sian Webster - forcing the audience to consider too the effects of the Arab Spring turmoil on not only scholarly works, but also the perception and position of women in academia and society in general.

An after-show talk with the actors and Dr Panić revealed that female astronomers remain a rare breed and that there is still much to be done to encourage girls to study, teach and lead science-based education in the field. Scientific heroines are needed to encourage girls to aspire to something great: in Nicolas’ words, to help them ‘find the co-ordinates of their lives’.

“We are all made of star stuff” and this performance is no different. Bell Burnell could just as well have been describing this performance (she has seen it and does approve, apparently!) as talking about the architecture of inter-stellar life itself.

The Scotsman

Traverse, Edinburgh; 20th November 2013

Reviewer: Joyce McMillan

FULFILMENT FOR WOMAN WITH STARS IN HER EYES

...in the end, as Jessica begins to guess at the crisis in Caroline’s life caused by her brother’s late marriage, and as her own conflicted life as astronomer, wife and mother reaches a frightening crisis of its own – the play begins to develop a powerful poetic momentum.

And that final intensity is reflected both in Gus Monro’s haunting design of star maps and scattered starlight, and in Siobhan Nicholas’s thoughtful and poignant performance as Caroline; the woman who gives up her own life to help her brother in his work, yet finally becomes a passionate astronomer in her own right, caught up in the swirling magic of the universe she has observed through her brother’s great telescopes, and determined to keep on exploring it, to the end.

“...an elegant, accomplished piece of theatre that showed the people at the end of the telescope to be as fascinating and complex as the universe they gaze on”.

The Argus - Brighton Fringe Festival

May 2013; The Old Market

“...an elegant, accomplished piece of theatre that showed the people at the end of the telescope to be as fascinating and complex as the universe they gaze on”.

Oxford Daily Info

Reviewer: Rosa

A gripping, complex narrative that is beautifully acted by the cast of three….A gem.

Waterloo Press

The Old Market, Brighton, May 30th 2013

Reviewer: Simon Jenner

Anyone acquainted with Siobhan Nicholas's Hanging Hooke will know something of the exhilarating intellectual and human passion unleashed in her plays.....

A superbly moving, compact and yes exhilarating play. It pushes at the bounds of speculation, re-visiting these with much of the force of their original discovery, and inimitably with Nicholas discovering something about the people who vie for the honour of being first in their field. Nicholas isn't content to dramatize it but question who did what, and what else was known. Nicholas has now written a brace of plays that constitute an oeuvre in themselves.

Crisp directing (The Company with Polly Irvin) combine with the high production values of Gus Munro's design and Neal McBride's lighting. It would certainly excel in the round of the Stephen Joseph, a future venue, and before it goes to The Dublin Festival of Curiosity, Greenwich Theatre is a mandatory last stop. Stella though should be on at the Cottesloe (or Dorfmann as it'll become) or indeed at The Minerva which hosted Hanging Hooke.

Stella is the best new play in toto, I've seen from a rising dramatist for many years.